From APIs to BPIs: Min-maxing the use of Sensitive Data

Today, most user data sits behind APIs. Whether its storage is delegated to an external entity (e.g., a social network), it's stored directly on a blockchain, or it remains on the user's device (e.g., browser history), third-party apps and services request access to that data via an API. But most often, users are not compensated directly for granting such access. This is the case even when the API itself may charge the third-party app for such access! Furthermore, once API access is granted, data is retrieved in its plaintext form. The extent to which that plaintext data is exposed is often at the discretion of the third party.

Defining Features of a BPI

To help us describe an alternative world in which third-party app and service developers need not force their users into a conundrum when it comes to their data, we introduce the notion of a blind provable interface (BPI), reflecting our point of view that BPIs are an extension and, eventually, an evolution of today's ubiquitous APIs.

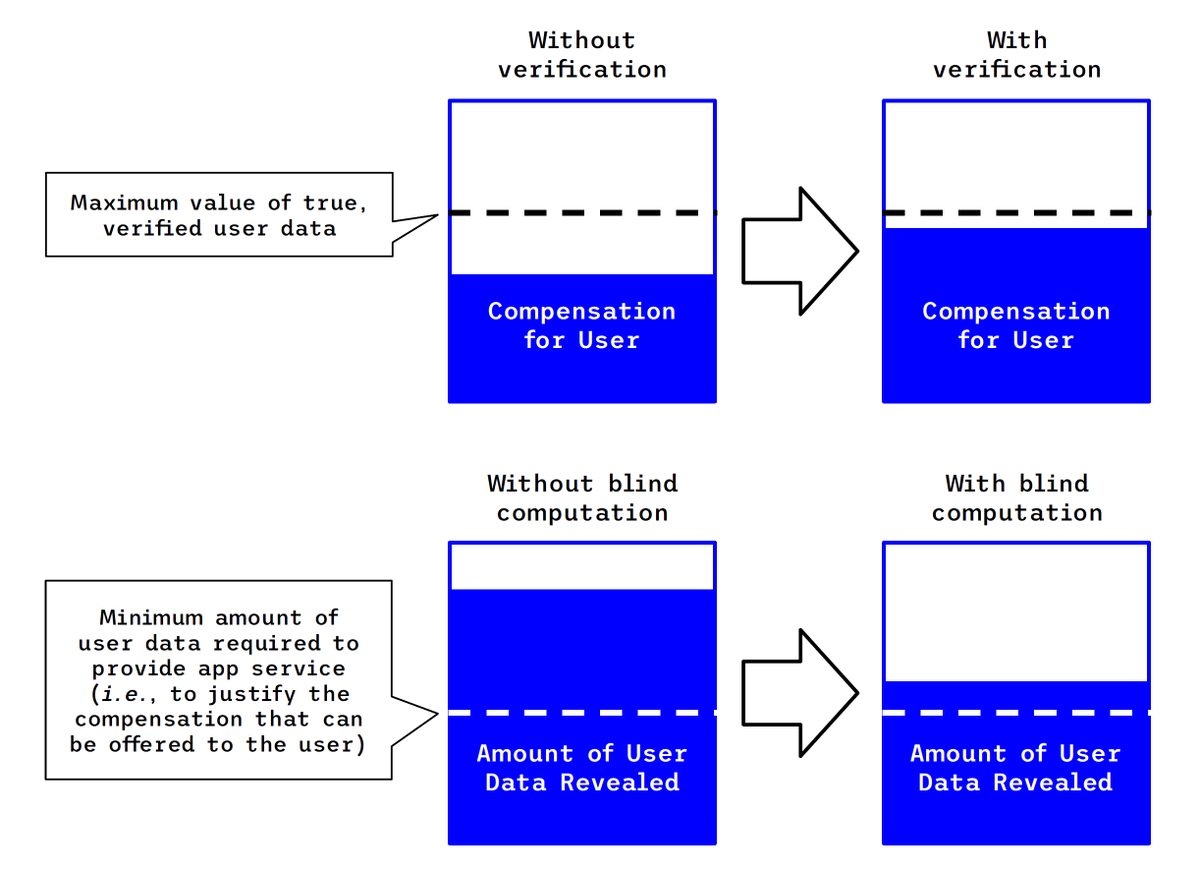

The three defining features of a BPI revolve around maximizing compensation users receive for the value of the minimal subset of their data that has enough utility to match that value. That is, a BPI should offer at least three defining features:

- User control and blind computation (revealing the minimum amount of data that has utility and commands compensation)

- Proof of data provenance, authenticity, and integrity (helping justify the maximum possible compensation for the revealed data)

- Mechanisms for compensating a user for granting API-like access to their data

The figure above illustrates these features visually. A user is usually asked by an app to delegate access to their data because that data has some value (whether directly or because it enables the app to provide a service for the user). A proof of where the data originates (its provenance), the identities of the participating entities that helped retrieve it (its authenticity), and that it hasn't been altered (its integrity) reduces the risk from the perspective of the app, thus nudging up the amount of compensation the user may expect. At the same time, leveraging blind computation allows the app to request access only to the data for which the app is willing to compensate the user (protecting the user's data and reducing the app's liabilities associated with unnecessary data access).

We see BPIs as something that can be introduced gradually, with early BPIs being simple wrappers over existing well-established APIs. Further below, we describe two such wrapper BPIs that support the Tickr app. In the future, APIs may be built as BPIs from the ground up using developer tools such as those offered by Nillion and other projects.

Wrapper BPIs via Key Delegation and Data Delegation

A wrapper BPI can be grouped into one of two categories depending on whether a user delegates their API key (and thus the responsibility of querying the underlying API) to a separate party or merely delegates their data to that party (with the user themselves performing the API queries). Each category has advantages and disadvantages; a given workflow may be better suited for one or the other.

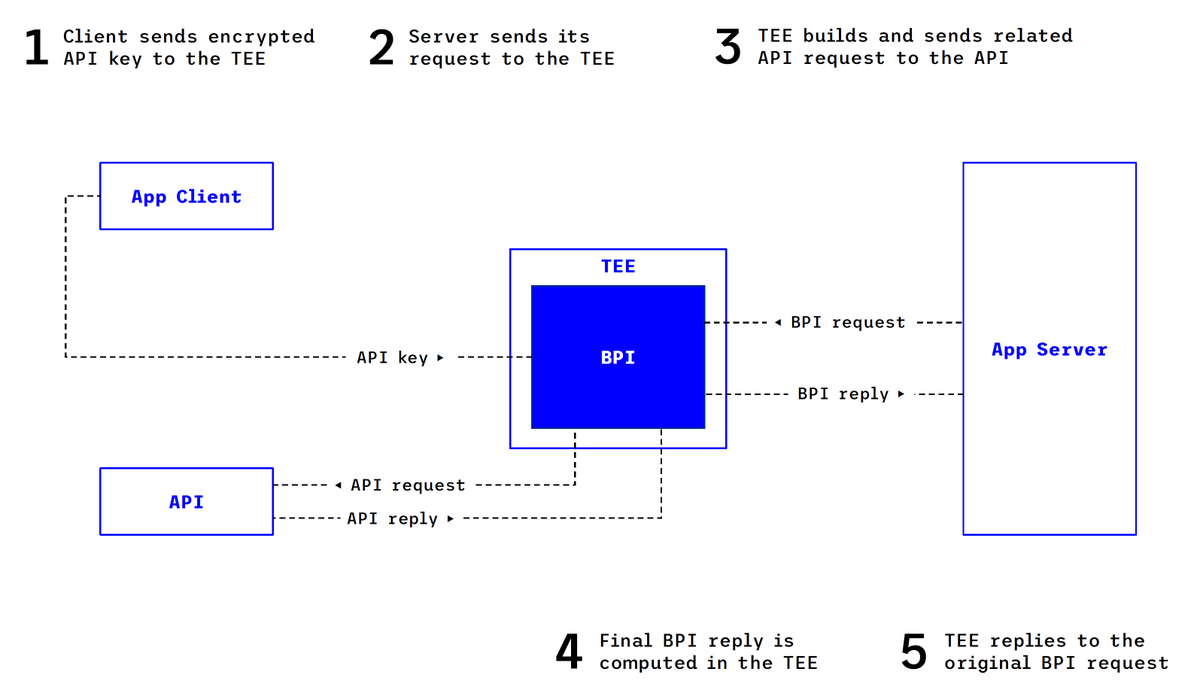

Key Delegation with TEEs

In what is arguably the simpler of the two variants, a BPI can be implemented by introducing a TEE instance that serves as an intermediary between an existing API and a third party. The user delegates their API key to code running inside a TEE instance, and that code can obtain the necessary data from the underlying API. From the perspective of a third-party app, a BPI service inside the TEE then serves as a substitute for the API. This BPI service minimizes data exposure by computing within the TEE only the outputs that are necessary to fulfill the request, generates an attestation that the input data was obtained from the original API, and ensures that the user is compensated.

An advantage of this variant is that it can be asynchronous: once a user delegates their API key to the TEE instance, they need not be present for the third party to query the BPI. Another advantage of this approach is that the BPI may aggregate data belonging to two or more distinct users and/or that has been obtained from two or more distinct source APIs at distinct times.

A disadvantage of this variant is that the user (or other parties to which the user delegates this responsibility) must oversee that the TEE performs only user-permitted requests.

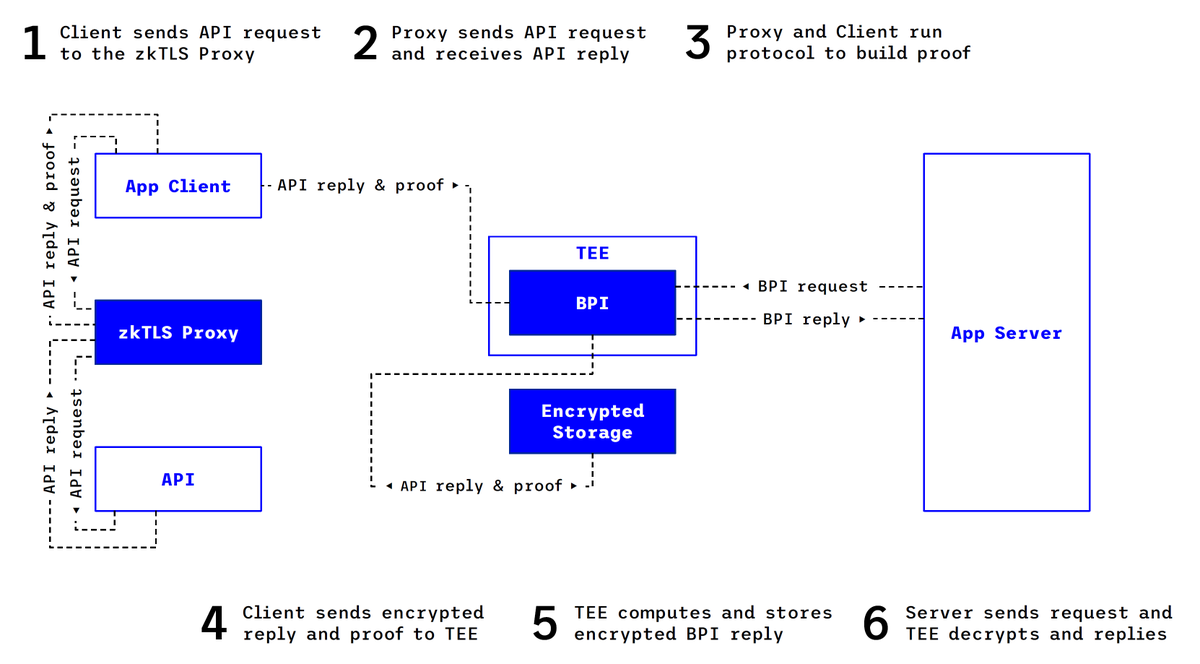

Data Delegation with zkTLS and TEEs

It is also possible to implement a BPI in which the user only delegates their data to a TEE instance. In this variant, a user obtains the data from an existing API using zkTLS. The user then delivers this data to a TEE instance together with the proof of the data's provenance. When the BPI service inside the TEE is queried by the third party, it can confirm the proof of the data's provenance, compensate the user, and perform computations that minimize the amount of data that is exposed.

An advantage of this approach is that the user need not delegate an API key to the TEE instance (which may represent too great a risk for the user) and solely determines which data is requested.

Disadvantages of this variant are its greater complexity (requiring more distinct software components to interoperate) and that the user must synchronously participate for each distinct request to the underlying API.

Building Towards BPIs

A range of existing projects are already working towards a world in which BPIs are commonplace. In this section, we acknowledge a few examples being built both by Nillion and other groups.

Tickr and Trading Data

Tickr (@Tickrdotapp) relies on both categories of BPI in its implementation. The integration with the Hyperliquid API is wrapped in a BPI that relies on key delegation: a backend running entirely inside nilCC allows users to connect their account/wallet so that their trading history can be retrieved in a private and verifiable manner. On the other hand, the integration with Binance is accomplished using data delegation: the zkTLS Binance flow leverages the @primus_labs Chrome extension to extract and verify trading data that is then forwarded to Tickr. That data can then be stored in encrypted form within nilDB.

Other Projects

A range of ongoing efforts and projects are building either components that can play a critical role in enabling BPIs or entire workflows that can be seen as fully working examples of BPIs. For example, x402 provides a standard way to compensate users for granting API access to retrieve their data. Reclaim Protocol (@reclaimprotocol) makes it possible to verify the source of data retrieved from an API, and Primus Labs (@primus_labs) can be viewed as a full-fledged BPI solution. More broadly, efforts to create privacy-enhanced interfaces for retrieving onchain transaction data can also be viewed as working towards a BPI-like future.

Ongoing Research

zkTLS has been a very active area of research recently, with multiple publications appearing in top-tier conferences. These focus on different TLS variants (versions 1.2 and 1.3), k-anonymity guarantees between multiple TLS servers, improved malicious two-party computation tailored to zkTLS, minimizing communication, and so on. One example is TLShare (a.k.a., TLS-share), the recent research collaboration between Nillion (@nillionnetwork) and Primus Labs (@primus_labs) that focuses on combining data from multiple clients under MPC and FHE. This not only works towards general-purpose zkTLS (by allowing private computations on verifiable data), but also allows combining data across multiple clients while keeping it private.

Looking Forward

APIs are ubiquitous and are the workhorses of the data-driven ecosystems found in both centralized SaaS and decentralized ecosystems. The concept of a BPI makes it possible to succinctly articulate exactly how APIs can evolve to better compensate users for their data while also protecting that data. Furthermore, this concept suggests a straightforward way to begin transforming existing ecosystems: first by creating BPI wrappers around existing APIs and then eventually assembling the toolchains that developers need to incorporate BPIs into the apps and services being built from the ground up. We at Nillion are looking forward to enabling both stages of this transition by building up the software tools and the decentralized infrastructure that can help make this happen.